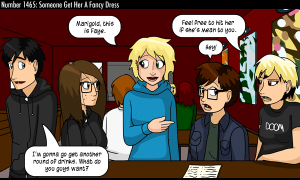

L to R: Marten, Marigold, Hannelore, Faye, Dora

OK, so I promised to review a few of my favorite webcomics for you lovely people. I’m starting off with my favorite webcomic, just to make it easy on myself (I am a lazy bum, after all).

First off, what makes Questionable Content (QC) my favorite webcomic? I’d say it’s my great love of quirk. You’re talking about the person who adores Pushing Daisies, Juno, and Firefly/Serenity. I ♥ quirk. QC is is a quirky, webcomic version of Friends. It’s also set in an alternate reality, one where computers walk around, interact with their owners, and have Roomba chariot races. Scientists live in space stations and people can dress up in Victorian costumes at their local bar. Squirrels also play a part . . . What’s not to love?

Does it have a storyline? Yes, but a pretty loose one that never really ends. It started off (drawn very simply) as a story of boy (Marten) meets girl (Faye). The two meet at a bar, with Faye being new in town and wanting friends but no romance, and Marten wanting romance. So, of course, a friendship begins, which develops into a roomateship when Faye burns down her apartment building while making toast. Faye introduces Marten to Dora, who owns Coffee of Doom (where Faye works). Marten and Faye eventually move into a larger apartment, where they meet their stalker, OCD neighbor Hannelore (raised in a space station). Once Faye states for sure that she could never be in a relationship with Marten, Dora jumps on him, and the two have been dating since then.

Over the course of the comic (running since ’03), we’ve met a wide array of characters, from Dora’s man-whore brother to the drunk trucker at the bar (who becomes a famous author of trashy romance and mystery novels) to the guy who comes into the coffee shop just to be made fun of by Faye to the pizza delivering PizzaGirl. The story mostly takes place in Coffee of Doom and in Faye & Marten’s apartment, but locations across the city (of Northampton, Mass) are also used. There’s the overall storyline that follows Marten and Faye (and Dora to a lesser extent), but that arc contains smaller stories of the people they meet. It’s pretty much Day-In-the-Life-Of type stories. Sometimes two week’s worth of comics will contain one conversation about music or love or World of Warcraft.

Would I read it if it was a book? Probably not. I’m not much on Day-In-the-Life-Of stories for novels, because I think books should be more focused than that, but for a webcomic it works well. Since the comic has no end in sight, the story should be the same. Plus, reading a 5-frame strip a day (5 days a week) keeps the storyline from getting too overwhelming. And if you feel the need to see the scope of the whole comic, then sit yourself down for 2 or 3 days and read the comic from beginning to end (yes, I’ve done it . . . more than once). Still, a full-comic read is not necessary to enjoy or appreciate the 5 frames-a-day format.

How’s the art? Fantastic, especially once you see the difference between the first and most current strips. Jeph Jaques (illustrator and author) has grown amazingly in the last six years, as both an artist and a writer. Unlike many webcomic artists who choose to keep their images simplistic (or even just at the same level they began the comic at), Jaques has used this outlet (and now his main source of income) to expand, learn, and create better art. The first strips were simplistically drawn, as most comics are, with basic coloring and very little shading. Over time, Jaques added little techniques and equipment that at the time of the change seemed pretty unnoticeable, but overall added a whole other dimension to the art.

How’s the writing? Jaques’s art is not the only talent of his to expand over the life of the comic. As he grew more confident in his writing and as his characters developed fuller personalities, the storyline grew more interesting, relateable, and thought-out. It went from stand-alone strips to a single storyline taking several weeks, or even months, to play out. HJaques has even gone to multi-arc format, where he’ll switch back and forth between two storylines or two groups of characters.

So this comic is awesome, but it can’t be perfect—what are the flaws? As with most of what you read in books or see on TV, the characters are all very good-looking and overly angsty. The looks thing can be ignored in books, but the comic tends disallow this. Even Faye, who is a more rounded person, is still considered “aerodynamically curvacious,” i.e. curvy in all the right spots.

As for the angsty issue, I suppose it’s just a side-affect of being an indie/hipster comic. They’re all angsty, right? Still, the problems the characters face tend to seem cutesy, or not all that bad. For instance, Hannelore, the OCD girl, sometimes stays up for days because she can’t stop counting, but she just comes into the coffee shop looking tired and everyone sends her to Faye/Marten’s apartment for a nap on their couch, where they later find her having hilarious romantic dreams about Indiana Jones. Perhaps you could consider it the author just trying to lighten up a bad situation, but even consequences that last through several story arcs still don’t really seem long-term. Still, at least they all do have problems of some sort (intamacy issues, freaky parents, OCD).

Webcomics tend to be rather NSFW (not safe for work, aka rated R), how does this one rate? For the most part, this is a pretty safe comic to read, but every once in a while something crazy pops up. There have been situations of people sleeping together, sexual references, and language (this is the one encountered most), but it’s not a regular thing, although I will say it’s gotten more NSFW within the past year. There is also a good bit of high school/college humor. If that’s something that worries you, wait till I review Punch’n Pie and Girl Genius, both are safe for all.

Rating: 9.5 out of 10 stars

My latest read, by Nobel-laureate and Portuguese author José Saramago, follows a small group of people trapped in an unnamed country stricken by a white blindness. This blindness affects everyone’s sight apart from the wife of an ophthalmologist—who was one of the first afflicted with the disease. The blindness comes without warning and is passed on through the slightest of contact. The first of the stricken are placed in an old mental hospital in hopes of containing the disease. Those interned in the hospital must learn to fend for themselves as they are left alone in an unknown place without any amenities apart from beds and erratically delivered meals.

My latest read, by Nobel-laureate and Portuguese author José Saramago, follows a small group of people trapped in an unnamed country stricken by a white blindness. This blindness affects everyone’s sight apart from the wife of an ophthalmologist—who was one of the first afflicted with the disease. The blindness comes without warning and is passed on through the slightest of contact. The first of the stricken are placed in an old mental hospital in hopes of containing the disease. Those interned in the hospital must learn to fend for themselves as they are left alone in an unknown place without any amenities apart from beds and erratically delivered meals. Potiki is a broken story about a broken people, or so you might guess from the first 20 or so pages of the novel. The narrative jumps from person to person and across time. Many of the main characters are disabled in one way or another, and the community they belong to is dying out. Not exactly the happy reading one usually hopes for in the get-away-from-the-world fictional stuff we tend to read for enjoyment. To argue for the other side, maybe reading about others’ problems and how they deal with them is a good way to get away from our own life issues. And that’s my argument for why this novel ultimately is a happy one, despite its brokenness—Potiki leaves you hopeful, both for the future of the characters and for your own future. If they can face the future, so can we, right?

Potiki is a broken story about a broken people, or so you might guess from the first 20 or so pages of the novel. The narrative jumps from person to person and across time. Many of the main characters are disabled in one way or another, and the community they belong to is dying out. Not exactly the happy reading one usually hopes for in the get-away-from-the-world fictional stuff we tend to read for enjoyment. To argue for the other side, maybe reading about others’ problems and how they deal with them is a good way to get away from our own life issues. And that’s my argument for why this novel ultimately is a happy one, despite its brokenness—Potiki leaves you hopeful, both for the future of the characters and for your own future. If they can face the future, so can we, right? review anything. I’m still in a reading rut, but I came up with a good book for review—Hugo Award-winning Rainbows End (as weird as it looks, there’s no apostrophe in Rainbows). My inspiration for this review is

review anything. I’m still in a reading rut, but I came up with a good book for review—Hugo Award-winning Rainbows End (as weird as it looks, there’s no apostrophe in Rainbows). My inspiration for this review is  Sorry for such a gap in postings, but I’ve been working up my nerve to review what is probably one of my favorite books in the world—Brideshead Revisited, The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder. As I type, I still really don’t know what I’m going to say. Though not an overly long tale (my copy sits at 368 pages), it’s chock full of some amazing plot lines, characters, and themes, and I don’t know that I can do the novel justice. But I guess I’ll just jump in and see where the river takes me.

Sorry for such a gap in postings, but I’ve been working up my nerve to review what is probably one of my favorite books in the world—Brideshead Revisited, The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder. As I type, I still really don’t know what I’m going to say. Though not an overly long tale (my copy sits at 368 pages), it’s chock full of some amazing plot lines, characters, and themes, and I don’t know that I can do the novel justice. But I guess I’ll just jump in and see where the river takes me.

characters will take up enough of your thoughts. Waugh’s writing pulls you in, and you completely forget about everything else when reading this novel. All that matters is the characters and the stories they tell.

characters will take up enough of your thoughts. Waugh’s writing pulls you in, and you completely forget about everything else when reading this novel. All that matters is the characters and the stories they tell.

Possessing a talent and imagination similar to perennial favorite Roald Dahl, Gaiman was meant for children’s lit. Like Dahl, Gaiman excels at truly creepy and imaginative children’s lit, which makes it great for readers who think they’ve outgrown the genre. These readers may be initially turned off by the illustrations that pepper the book, but I believe the illustrations add to the story. Illustrated by long-time Gaiman collaborator Dave McKean, the art is black/grey and white, rough but detailed, and slightly disproportionate in nature, adding to the spookiness of the tale.

Possessing a talent and imagination similar to perennial favorite Roald Dahl, Gaiman was meant for children’s lit. Like Dahl, Gaiman excels at truly creepy and imaginative children’s lit, which makes it great for readers who think they’ve outgrown the genre. These readers may be initially turned off by the illustrations that pepper the book, but I believe the illustrations add to the story. Illustrated by long-time Gaiman collaborator Dave McKean, the art is black/grey and white, rough but detailed, and slightly disproportionate in nature, adding to the spookiness of the tale.

I’ve had Pascal’s Wager in my collection since high school and just recently it seemed like a good idea to reread it. It’s one of those books you reread when you’re in a sort of pseudo-philosophical mood, but aren’t up for something heavier like Camus or Kant. Not to say that Rue’s book is pseudo-philosophical. I’d instead call it philosophy light, perhaps like Sophie’s World—good for those entering or thinking of taking Philosophy 101. Instead of being absurdist and nihilistic in nature, however, Rue chooses theology as her means of finding answers, and she gets it done without being preachy or heavy-handed.

I’ve had Pascal’s Wager in my collection since high school and just recently it seemed like a good idea to reread it. It’s one of those books you reread when you’re in a sort of pseudo-philosophical mood, but aren’t up for something heavier like Camus or Kant. Not to say that Rue’s book is pseudo-philosophical. I’d instead call it philosophy light, perhaps like Sophie’s World—good for those entering or thinking of taking Philosophy 101. Instead of being absurdist and nihilistic in nature, however, Rue chooses theology as her means of finding answers, and she gets it done without being preachy or heavy-handed.